Multiplatform Content (ADMA6009)

Research

Transmedia:

Transmedia storytelling unfolds across multiple platforms, with each medium contributing uniquely to a unified story world. According to Jenkins (2006, p. 95) “Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience”. Central to this are Jenkins’ “three C’s” of transmedia—Content, Community, and Communication—emphasising audience engagement, participatory culture, and collaboration (Jenkins, 2009). For instance, The Matrix franchise expanded its story through films, video games, and comics, encouraging fans to actively engage and decode hidden elements in forums, exemplifying Jenkins’ concepts of Participatory Culture and Collective Intelligence.

Jenkins also explores how Media Convergence blends traditional and digital formats to deepen audience experiences. This approach should inform my project which will span platforms like documentary film, 360 video, and photo books to highlight accessibility in adventure. By embracing transmedia principles, my project will aim to transform audiences from passive viewers into active participants, fostering reflection and dialogue about inclusivity in outdoor spaces while creating a cohesive and immersive narrative.

Critically Review Platforms:

The success of contemporary storytelling and engagement strategies depends heavily on the appropriate use of media platforms. Each platform offers distinct strengths and limitations, requiring careful consideration when selecting the right medium for a given message or audience. This review explores digital, physical, and immersive media types, assessing their potential for impact, accessibility, and audience engagement.

Digital Media

Digital platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok enable global reach and immediacy, each excelling in different formats. Social media platforms also offer an opportunity for audience participation, this is supported by Evans (2011, p. 22) who states that “New media platforms allow for a dynamic relationship between producers and audiences, fostering daily interaction and participation”. YouTube supports long-form content for detailed storytelling, while Instagram and TikTok excel at short, visually engaging content with interactive features like polls and hashtags (Jenkins, 2006; Evans, 2011). Campaigns such as #ShareACoke highlight the power of social media to foster community-driven initiatives.

However, challenges like accessibility and oversaturation persist. Inadequate support for users with disabilities, such as a lack of captions or audio descriptions, limits inclusivity (Ellcessor, 2012). Additionally, capturing attention requires significant investment in quality and promotion due to content oversaturation.

Physical Media

Physical media, such as photobooks and prints, creates a tangible, emotional connection with audiences. Products like photobooks often serve as lasting keepsakes, reinforcing narratives in a way digital media cannot. They also excel in targeted contexts, such as exhibitions or cafés, offering perceived permanence and value (Berger, 2018).

However, physical media is less scalable, with high production costs and limited geographic reach. Accessibility is also a concern unless inclusive measures, like braille alternatives, are implemented.

Immersive Media

Immersive media, including 360 video, VR, and soundscapes, offers empathetic storytelling by engaging multiple senses. For example, the UN’s Clouds Over Sidra VR experience highlighted the life of a Syrian refugee, fostering deep audience connection. This is reinforced by Murray (2016, p. 47) who says “The power of virtual environments lies in their ability to evoke ‘active engagement’ and ‘emotional investment’ from users”, further supporting that immersive media is a powerful tool for igniting empathy within viewers.

Despite its potential, immersive media requires expensive equipment and specialised skills, limiting accessibility and scalability. These barriers can make it challenging for smaller projects or organisations to adopt effectively.

By leveraging the strengths of each medium while addressing accessibility challenges, storytellers can craft inclusive and impactful narratives that resonate across diverse audiences.

Conclusion

Each media platform type offers unique strengths and challenges. Digital platforms excel in reach and interactivity but require thoughtful accessibility measures to avoid excluding audiences. Physical media provides a tangible, personal connection but is often constrained by costs and distribution. Immersive media offers unparalleled opportunities for empathy and engagement but faces barriers in accessibility and scalability. A successful strategy will often combine these platforms, leveraging their respective strengths while addressing their limitations to create a cohesive and impactful audience experience.

Accessibility:

In Adventure

Accessibility in adventure ensures people of all abilities can engage meaningfully, promoting dignity and equality. Ross Head (2024) of Cerebra underscores this, stating, “Accessibility in adventurous activity is not just about participating—it’s about engaging as closely as possible to able-bodied individuals, with dignity.” This sentiment is echoed by Darcy & Dickson (2009, p. 35), who say that “Accessibility is not just about participation; it is about providing equitable opportunities for engagement”. Adaptive equipment like seated paddleboards exemplifies inclusive design, fostering autonomy. Research by Lundberg et al. (2011, p. 153) highlights how adaptive sports enhance self-esteem and reduce stigma, stating that “Participation in adaptive sports has been shown to enhance self-esteem, foster independence, and reduce stigma associated with disability”. Although barriers like funding and provider training remain (Darcy & Dickson, 2009).

Transmedia storytelling can bridge gaps in awareness by amplifying these initiatives. Platforms like documentary films, 360 videos, and social media foster empathy and engagement, as seen in Jenkins’ (2006) participatory culture model. By leveraging transmedia, organisations such as Cerebra can raise awareness, inspire systemic change, and make adventure accessible to all.

For Viewers/Consumers of Media

“Accessibility must be recognised as a central component of participation in digital media, requiring proactive measures like captioning and audio descriptions” (Ellcessor, 2012, p. 45). Features like captions, audio descriptions (AD), and British Sign Language (BSL) translations align with my projects inclusivity goals (Sellwood & Coldhouse Collective, 2024). Captions aid deaf viewers by including dialogue and sound effects, while AD bridges gaps for visually impaired audiences (Ellcessor, 2012). These tools enhance inclusivity and foster engagement across platforms, from documentaries to 360 videos.

In a transmedia context, tailored accessibility features maintain inclusivity without compromising the audience experience. Jenkins’ (2006) participatory culture emphasises collaboration, ensuring all viewers can engage as active participants. For my project, integrating accessibility across all media—from captions to alt text—ensures the story reaches and resonates with everyone.

Ableism

My project will commit to addressing ableism, which assumes disability as a deficit requiring correction. Rooted in the medical model, ableism perpetuates exclusion and stigma (Everyday Ableism, 2024). Key ethical principles include:

Key ethical considerations include:

• Informed Consent:

Participants are collaborators, fully informed about the project’s purpose and distribution. Consent is confirmed throughout.

• Respectful Representation:

The narrative avoids stereotypes, focusing on abilities and shared experiences.

• Empathy without Exploitation:

The project builds empathy without sensationalising personal stories, ensuring contributor-led narratives.

• Cultural Sensitivity:

It considers the diverse intersections of disability with cultural and socioeconomic factors.

Ideate: My Project

Title

Beacon: Adventure Without Limits

The name “Beacon” was chosen to reflect Jenkins’ concepts of Communication and Community. A beacon symbolises connection and guidance, aligning with the project’s goal to share stories of accessible adventure and foster a sense of belonging. It serves as a unifying symbol, bringing people together and inspiring collective action through shared experiences.

The slogan “Adventure Without Limits” was chosen to emphasise inclusivity and possibility, reflecting the brand’s mission to make adventure accessible to everyone. It challenges traditional perceptions of adventure by promoting activities that accommodate diverse abilities, fostering empowerment and a sense of belonging for all participants.

Synopsis

Beacon: Adventure Without Limits will be a multi-platform media project celebrating those who make adventure accessible to all. It will highlight the transformative work of organisations such as Cerebra and Ski 4 All, showcasing how adaptive activities like skiing, surfing, and hiking empower individuals with disabilities to experience the outdoors with dignity, independence, and a sense of community.

Through platforms including a documentary film, 360 video, soundscapes, photobooks, and collectible tickets, Beacon will tell inspiring stories of innovation in adaptive equipment and the profound impact of inclusive adventure. Designed with accessibility at its core, the project will raise awareness, foster empathy, and honour the individuals and organisations breaking barriers to outdoor exploration.

Stakeholders:

The primary stakeholders in Beacon: Adventure Without Limits are Ski 4 All Wales and Cerebra, both organisations dedicated to empowering individuals with disabilities through innovative and inclusive approaches.

Ski 4 All Wales provides accessible skiing opportunities, fostering independence, confidence, and joy through adaptive equipment and tailored instruction. Cerebra, a charity specialising in the design of products for individuals with brain conditions, develops innovative solutions that enable participation in activities often deemed inaccessible. By showcasing the work of these organisations, Beacon aims to raise awareness, generate community support, and secure funding. The project benefits these stakeholders by highlighting their impact, driving engagement from broader audiences, and creating a platform for storytelling that reflects their commitment to accessibility and inclusion.

Ideas for Strategy:

1 - Immersive Escape Room

One of the initial ideas for Beacon: Adventure Without Limits was to create an immersive escape room as part of a multi-platform, transmedia project. The escape room concept had the potential to build empathy by placing participants in scenarios that simulated some of the challenges faced by individuals with disabilities. However, this idea was ultimately set aside due to the practical and ethical challenges of ensuring it was fully accessible to all participants.

2 - Website/Social Media/Digital Marketing Campaign

Another potential approach for Beacon: Adventure Without Limits was to develop a website as the central hub, supported by a social media and digital media campaign. This option would have facilitated wide-reaching engagement and provided convenient access for a broad audience. However, this idea was not pursued because a more interactive and personal approach was deemed to create a greater impact.

3 - Immersive Event (Displaying Video, Sound and photographic content in a gallery style format).

The chosen approach for Beacon: Adventure Without Limits is an immersive event that showcases video, sound, and photographic content in a gallery-style format. This strategy was selected because it offers a powerful, multisensory experience that allows attendees to engage deeply with the themes of accessibility and adventure. By bringing audiences together in a physical space, the event fosters a sense of community and encourages meaningful connections with the stories and experiences being shared.

Strategy Explanation

An example of a video that uses sound to convey the challenges faced by individuals with accessibility needs, effectively building empathy in the viewer.

The core strategy for Beacon: Adventure Without Limits is to utilise a combination of physical and digital media to engage audiences and encourage reservations for a collectible ticket to an immersive event. This event is designed to build empathy by placing attendees in the perspective of participants engaging in adaptive accessible adventure activities, such as skiing, surfing, and hiking. Immersive storytelling techniques, including 360 video and soundscapes, will highlight the physical challenges and emotional triumphs of these experiences, fostering a deeper connection with the audience. Research supports the use of immersive media in creating empathy by simulating real-life experiences and enabling audiences to understand different perspectives (Murray, 2016; Milk, 2015). Murray (2016, p. 82) even goes as far as to say that “Virtual environments allow users to inhabit another person’s reality, offering a deeper understanding of their experiences” and Milk (2015) refers to immersive media as an “empathy machine”.

Beacon employs a range of conceptual media types, each designed to serve a specific role within the project while contributing to its broader, long-term goals. These media forms align with Jenkins’ (2006) transmedia storytelling framework, using Communication to convey key narratives, fostering Community through audience interaction, and ensuring the project’s sustainability beyond the immersive event.

Digital Media

Digital media is foundational to Beacon’s strategy, with its potential for broad reach and interactivity allowing it to engage audiences before, during, and after the immersive event.

• Documentary-style YouTube video: Planned to feature Ross Head and his work with Cerebra, this video will explore the transformative impact of adaptive equipment like sit-skis and surfboards. Testimonials from participants and stakeholders will enrich the narrative, creating an emotional and educational resource. Aufderheide (2007, p. 15) makes the point that “Documentary films have the unique ability to inform, inspire, and mobilise audiences by presenting real-world issues”. Beyond its role in raising awareness before the event, the video will serve as a long-term advocacy tool for stakeholders, helping them promote inclusivity in adventure activities.

• Social media content: Platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok are envisioned to share short-form videos, participant stories, and behind-the-scenes content. These posts will drive community engagement and encourage ticket reservations, while also acting as a gateway to other media. After the event, these platforms will sustain audience interaction, enabling continued storytelling and broadening the project’s reach (Jenkins, 2006).

• Blog posts: In-depth articles hosted on the project’s website will provide insights into accessibility in adventure, participant journeys, and adaptive equipment design. These blogs aim to complement the immediacy of social media with deeper storytelling, while also acting as an archive for future audiences to explore (Ritchin, 2013).

• Interactive digital platforms: Features like live-streamed events, polls, and Q&A sessions with Ross Head will engage audiences actively, and as Murray (2012, p. 104) says, this will “transform the audience from passive recipients into active participants, shaping their experience and engagement” within the project. These interactive elements aim to create a dialogue that fosters long-term engagement and supports a participatory culture.

Physical Media

Physical media will create a tangible connection between the audience and the project, providing a means of engaging local communities while reinforcing Beacon’s identity.

• Photo prints: Proposed to showcase emotive moments of participants engaging with adaptive equipment, these prints will be displayed in local spaces such as cafés, UWTSD campuses, and outdoor centres. By offering a visual narrative within these familiar settings, the prints aim to inspire reflection and promote local awareness. “Photographs as physical objects carry a permanence that digital images often lack, creating lasting connections with their audiences” (Edwards, 2006, p. 53).

• Merchandise: Branded items such as T-shirts, caps, and reusable water bottles will not only promote the project but also provide an additional revenue stream for stakeholders like Ski 4 All and Cerebra. These items will carry Beacon’s identity beyond the event, creating long-term visibility (Wheeler, 2017).

• Collectible tickets: Serving as both functional entry passes and keepsakes, the tickets will be designed to leave a lasting impression on attendees. Their role extends beyond the event, as they become mementos that encourage continued reflection and discussion about the project (Sobchack, 1992).

Immersive Media

Immersive media will play a central role during the event, creating empathetic and engaging experiences that align with the project’s themes of inclusivity and adventure.

• 360 video: Planned to capture adaptive activities from the participant’s perspective, this video aims to immerse viewers in the experience of sit-skiing or surfing. By fostering empathy and understanding, the 360 video aligns with Monaco’s (2009) perspective that immersive storytelling deepens emotional connections. Its adaptability for VR platforms also ensures long-term engagement opportunities.

• Soundscapes: Combining natural sounds, participant reactions, and narration, the soundscapes are designed to evoke emotion and transport audiences into the world of accessible adventure. Rabiger and Hurbis-Cherrier (2020, p. 67) state that “Sound design has the power to evoke emotions and transport listeners to entirely new environments”, I think this concept is a vital component to retain viewer engagement.

• Photo and video installations: Curated displays of images and video excerpts will contextualise adaptive activities and highlight personal stories. These installations aim to connect audiences to the participants’ experiences, creating a reflective space that extends the impact of the event (Bordwell & Thompson, 2017).

Each media type is designed with longevity in mind, ensuring Beacon’s impact continues beyond the immersive event. Digital platforms provide ongoing resources and engagement opportunities, while physical media fosters local awareness and emotional resonance. Immersive media creates a powerful, empathetic experience that leaves a lasting impression, encouraging advocacy and participation in accessible adventure. Together, these media types establish Beacon as a sustainable initiative that continues to inspire change and promote inclusivity.

Character & Connector

At the centre of the strategy are the Beacon logo and a dynamic QR code, both of which ensure cohesion across media types:

• The logo acts as a unifying “character,” connecting all platforms and marking each piece of media as part of the Beacon brand. Its consistent presence reinforces brand recognition and community identity.

• The dynamic QR code links audiences to a central landing page that serves as a hub for all media. This page provides direct access to the YouTube video, social media content, and blog posts, while also offering a convenient way to reserve tickets or purchase merchandise. Unlike static QR codes, dynamic codes allow for updates to the linked content and provide analytics to track audience engagement (QR Code Generator, 2024).

By combining these physical and digital elements with immersive event experiences, Beacon creates a cohesive and impactful transmedia campaign. Jenkins (2006) highlights the importance of participatory culture in transmedia storytelling, and this strategy embraces that principle by enabling audiences to engage deeply with the narrative, fostering empathy, and inspiring action. This approach not only raises awareness but also generates funds for stakeholders such as Cerebra, ensuring the project’s long-term impact.

I created this diagram to help show my initial thoughts on my strategy - on reflection I plan to allow for more than 1 month for the time span.

Target Audience for Beacon

Beacon’s diverse target audience aligns with its goal to raise awareness about accessible adventure, foster empathy, and generate stakeholder support. Key segments include:

1. Local Community Members

• Who: Residents, including families, outdoor enthusiasts, and community event attendees.

• Why: Accessible physical media like photo prints in local spaces (cafés, UWTSD campuses, outdoor centres) connects with individuals who may not engage online. The immersive event offers hands-on interaction, enriching their experience (Shah, 2021).

• How to Reach: Physical media in public spaces for visibility; social media and local outreach to guide them toward ticket reservations and digital engagement (Jenkins, 2006).

2. Family and Friends of Participants

• Who: Relatives and associates of project participants, including those featured in adaptive adventures and stakeholders like Ross Head.

• Why: Their emotional connection drives support and amplifies the project’s message. Stories that evoke empathy are proven to increase engagement (Green & Brock, 2000).

• How to Reach: Share stories via digital media (YouTube, social platforms) and offer tangible engagement through collectible tickets and merchandise.

3. Accessibility Advocates and Professionals

• Who: Adaptive sports coaches, educators, and disability advocates promoting accessibility.

• Why: Aligned with Beacon’s mission, they can amplify the message and integrate insights into their work. Highlighting best practices in accessibility inspires this audience (United Nations, 2022).

• How to Reach: Documentary-style videos and blog posts showcasing adaptive equipment design and participant testimonials resonate with their professional interests.

4. Contributors and Stakeholders

• Who: Organisations and individuals supporting the event, such as Cerebra, local businesses, and sponsors.

• Why: Direct investment in the project’s success aligns with their goals of raising funds and awareness. Stakeholders value updates that clearly demonstrate progress and impact (Freeman, 1984).

• How to Reach: Engage through direct outreach, exclusive media previews, and branded merchandise updates.

5. Broader Online Community

• Who: Global audiences passionate about adventure, inclusivity, and transmedia storytelling.

• Why: Their participation amplifies Beacon’s reach through content sharing and discussions, supporting the mission globally. Storytelling on social media fosters emotional connection and broadens reach (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

• How to Reach: Leverage social media, interactive digital platforms, and QR codes to drive traffic to Beacon’s central landing page.

Rationale for Audience Selection

Beacon targets a blend of emotional, practical, and professional connections:

• Local communities and participant families form a strong grassroots foundation.

• Professionals and contributors amplify impact through networks and resources.

• Broader online audiences ensure global reach, fostering ongoing awareness and support for accessible adventures.

This strategy ensures immediate and lasting engagement, making the project impactful both locally and beyond.

Logo & Branding

The logo for Beacon: Adventure Without Limits acts as a core identifier for the brand, tying all media outputs together and creating a consistent visual identity across platforms. Designed with bold, symbolic elements, the logo combines the imagery of a flame, representing a beacon as a guiding signal, with flowing blue lines that signify water, aligning with the project’s connection to outdoor adventure and nature. Its minimalist yet impactful design ensures adaptability across both digital and physical media while remaining recognisable to audiences.

Iterative Development Process

The logo development followed an iterative process, allowing for continuous reflection and refinement. The first version used Windsor Pro font, chosen for its bold and legible qualities, which are ideal for minimalistic designs (Lupton, 2014). It featured fire imagery with a red and black colour scheme, intended to create a strong visual identity.

Upon review, I felt the design resembled branding for a gas engineer. During a lecture in November, peer feedback noted that the fire imagery lacked clarity and didn’t resonate with the intended themes. This prompted a redesign to better align the logo with its purpose.

To improve the design, I replaced red with orange, a color associated with warmth and energy, and black with blue to symbolize water and evoke trust and calm (Eiseman, 2000). The use of contrasting colors enhanced the logo’s visual appeal by making key elements stand out more effectively (Lidwell et al., 2010).

Through reflection and feedback, and by applying principles of font theory and color contrast, I developed a refined logo that better represents outdoor adventure, community, and hope, while maintaining a bold and professional design.

Adaptations for Versatility and Accessibility

To ensure the logo’s effectiveness across various platforms and applications, I created multiple versions with different font colours and colour combinations. These adaptations allow the logo to maintain its impact and legibility against a range of background colours. For example, lighter font colours are used on darker backgrounds, while darker tones ensure clarity on lighter surfaces. This flexibility not only enhances the visual appeal of the logo but also improves accessibility by ensuring all versions are clear and easy to interpret for individuals with visual impairments or colour perception difficulties.

QR Code

The QR code is a pivotal interactive element in Beacon: Adventure Without Limits, designed to enhance audience engagement and accessibility. Its circular design, outlined in vibrant orange, aligns with the brand’s logo and ensures a visually cohesive identity across all platforms. The high-contrast design and the clear “SCAN ME” instruction make it easy to identify and use, ensuring inclusivity for diverse audiences. These design choices reflect the project’s commitment to accessibility and user-friendly interaction.

Functionally, the QR code directs users to a custom landing page hosted at Taplink, which acts as a central hub for audience interaction. The QR code is integrated into all media types, including promotional materials and event collateral, ensuring a seamless link between the physical and digital aspects of the project (Jenkins, 2006).

Landing Page

The landing page plays a critical role in facilitating audience engagement before, during, and after the event. Before the event, it includes a “Get Your Ticket” button that currently prompts users to send an email to reserve their ticket. In the final version, this will be replaced by a digital form where users can enter their details, such as name and address, to be added to a database. This streamlined process will allow ticket reservations to be processed digitally, with the physical collectible tickets posted to attendees.

Post-event, the landing page will evolve to focus on fundraising and continued audience engagement. Visitors will have the opportunity to purchase Beacon-branded products, such as merchandise, prints, or the photobook, with all proceeds supporting stakeholders like Ski 4 All Wales and Cerebra. This dynamic functionality ensures the landing page remains relevant and impactful, serving as both an operational tool and a resource for raising awareness and funds.

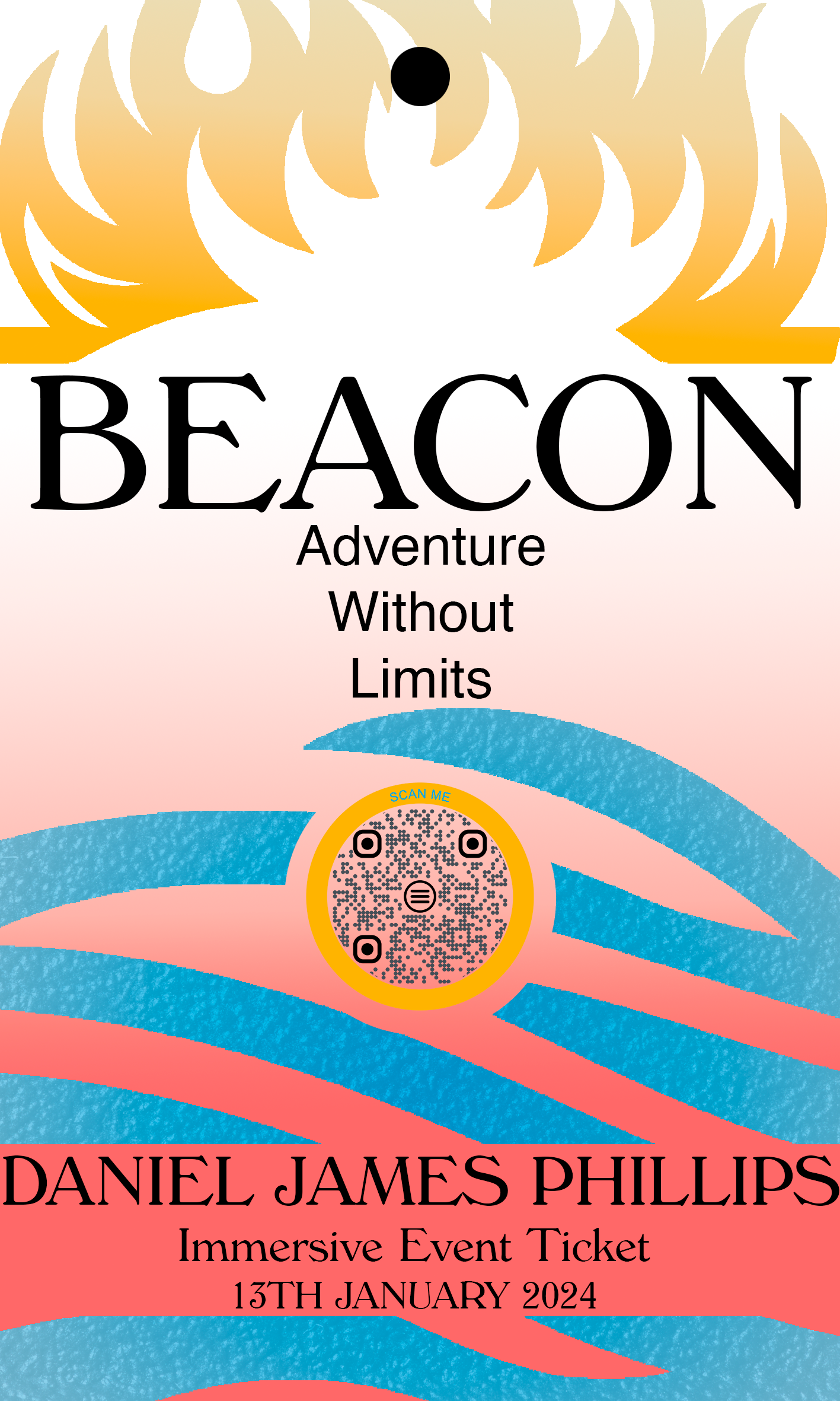

Platform 1: Collectable Ticket

The collectible ticket design began with a sketch incorporating key branding elements such as colours, shapes, and fonts to ensure visual continuity and reinforce brand identity (Landa, 2021). This approach minimised the need for a prominent logo, as the design itself communicates the brand effectively.

Textures and material finishes were carefully considered to enhance the ticket’s sensory appeal and perceived value as a keepsake (Norman, 2013). Inclusivity was a priority, with Braille considered to ensure accessibility for visually impaired users, adhering to universal design principles (Mace, 1998). Both sides of the ticket feature engaging visual and textural elements, reflecting a holistic and thoughtful approach to design (Heller, 2015).

The second iteration of the collectible ticket was developed in Photoshop, refining the design with the brand’s established colour palette, typography, and shapes. “Effective branding relies on consistent use of colour, typography, and imagery to create a unified and recognisable identity” (Landa, 2021, p. 145). Gradients and dynamic patterns were introduced to create a visually engaging and polished layout.

Key details, such as the event date and ticket type, were added in this version to ensure functionality and clarity. Helvetica was selected for this text, offering a clean and modern look that complements the overall design. This phase also focused on balancing aesthetic appeal with practical considerations, ensuring all information is prominently displayed and easy to read (Norman, 2013).

The final iteration of the collectible ticket showcases customisable features, such as the attendee’s name, reflecting principles of personalisation and engagement as highlighted in Convergence Culture (Jenkins, 2006). The font for both the personalised information and key details, such as the event date, was updated from Helvetica to Windsor Pro, enhancing the ticket’s aesthetic appeal and aligning with the overall design.

This version also incorporates tactile and sensory elements, with textured features designed to provide a visually and physically engaging experience, as Norman (2013, p. 203) explains, “Design should not only look good but also feel good, engaging multiple senses to create a richer user experience.” A QR code was added, linking seamlessly to all other media in this transmedia project, reinforcing the interconnectedness of the brand’s multi-platform presence (Landa, 2021). Together, these enhancements ensure the ticket serves both as a functional item and an extension of the overall brand experience.

Platform 2: Photographic Images (Print & Digital)

To visually support the Beacon project, I developed photographic prints and digital images that highlight key people, equipment, and activities involved in accessible outdoor adventure. These images were designed to feature in a digital gallery, photobook, and physical prints, creating a more interactive and impactful experience for viewers.

The process began with gathering example images to inspire the composition and style of the project. These examples guided my focus on capturing three core elements: portraits of key figures (e.g., Ross Head), action shots of participants, and detailed product images of the adaptable kit. This initial planning phase emphasised creating a tangible product, in the form of photographic prints or a photobook, that would resonate emotionally with audiences while being accessible across various locations such as cafés, UWTSD campuses, and local outdoor centers.

https://www.snow-online.com/ski-resort/whitetail-mountain-resort_images.html

https://www.in-gearmedia.com/photography/product-photography

https://ucan2magazine.co.uk/days-out/blue-horizons/

https://michaelwharley.com/make-space-environmental-portraits-artists/

The first photography focused on action photography at Pembrey Ski Slope, documenting participants with Ski 4 All in dynamic and engaging scenarios. These images aimed to capture the energy and accessibility of the activity, aligning with the project’s core themes. This session established the project’s visual tone, prioritising an emotional connection and showcasing participants and instructors in a positive and inspiring light.

The next session focused on photographing Ross Head in his workshop, creating a personal connection with one of the project’s key characters. These images aimed to highlight his role in designing adaptive equipment, aligning with the project’s core themes of innovation and accessibility.

Iteration 1: Reflecting on this in-camera, I determined that the framing and composition were poor, as Ross appeared too small within the frame. According to Kobre (2016), effective visual storytelling requires key subjects to be prominently featured to draw the viewer’s attention and convey their importance. Given Ross’s pivotal role in the narrative, it became clear that he should be positioned more prominently, ensuring he is ‘front and centre’ to align with the project’s storytelling goals.

Iteration 2: I readjusted my composition and later cropped to position Ross as the central point of the frame, enhancing his significance within the imagery and improving the overall composition. Finn Beales (2021) reinforces the importance of using composition to draw attention to key subjects, ensuring they are visually prominent to strengthen the narrative impact. By centering Ross, I aligned the framing with this approach, creating a more engaging and purposeful image.

A subsequent session with Ski 4 All shifted focus to capturing both portraits and product shots. This session allowed for a more detailed exploration of the adaptive equipment used in outdoor adventure, highlighting the innovative designs and their significance to the participants. These images balanced technical detail with storytelling, ensuring they aligned with the broader goals of the project.

Throughout the process, I explored various styles and decided on a black-and-white aesthetic for all images. This choice removed distractions caused by color and created a timeless, cohesive look. The monochromatic style also evoked a sense of nostalgia and emotional depth, which felt appropriate for the project’s themes and audience.

The photographs are designed to be displayed collectively, creating a layered and immersive experience that highlights the variety of roles and contributions within accessible adventure. This approach honours all involved, from participants to facilitators, while aligning with the project’s goal of fostering empathy and awareness. By presenting these images as an interconnected narrative, the audience gains a more comprehensive understanding of what accessibility in adventure truly entails.

I printed, cut, and framed images for display and will seek feedback from stakeholders.

Platform 3: Youtube Video

I chose to interview Ross Head for the YouTube video to provide viewers with deeper insights into his work with Cerebra and how it aligns with the project’s themes of accessibility and adventure. The Cerebra office was selected as the location, with careful consideration given to the framing and background to visually reinforce the key narratives discussed. This decision aligns with Bordwell and Thompson’s (2017) emphasis on using mise-en-scène to enhance storytelling and provide context through visual elements.

The composition, tempo, and overall feel of this video were directly informed by previous work I’ve created, reflecting my developing style.

During filming, I utilised a two-camera setup to capture both wide and close-up shots, ensuring visual variety and smoother transitions during editing. This approach reflects Rabiger and Hurbis-Cherrier’s (2020) guidance on creating dynamic compositions to maintain audience engagement and visual continuity. To steer the conversation toward the project’s core themes, I asked targeted questions designed to elicit responses that aligned with the narrative goals, a technique Rabiger also highlights as essential in documentary filmmaking: “Carefully crafted questions can elicit responses that align with the film’s narrative goals while fostering a sense of authenticity” (Rabiger and Hurbis-Cherrier, 2020, p. 314).

Platform 4: Immersive 360 Video

For the 360 video, I recorded from the instructor’s perspective using a chest-mounted camera, adopting a POV-style approach to immerse viewers in the experience of adaptive adventure. This decision aimed to help potential participants overcome fear of the unknown by providing an authentic view of the activity. The camera was left running during multiple descents of the ski slope to capture a range of footage, allowing flexibility in the editing process to select the most dynamic and engaging moments (Monaco, 2009).

Captions were refined during post-production, with multiple iterations tested to ensure they were legible and positioned without obstructing key visuals. By addressing these technical and compositional challenges, the 360 video was optimised for both immersive and VR formats, enhancing its accessibility and ensuring it aligned with the project’s goals of fostering empathy and understanding.

Original Caption position was not viewable on Immersive Room Screens.

Amended Caption Position to be more central so that they appeared on the immersive screen without being cut off.

Platform 5: Immersive Soundscape

To create the soundscape, I used a microphone alongside the 360 camera to capture authentic audio from the ski slope, including environmental sounds and the interactions between the instructor and participant. This audio, recorded during the same session as the 360 video, ensures consistency across media types, creating a cohesive narrative that enhances audience understanding of accessible adventure. The soundscape incorporates key auditory elements, such as the rustling of equipment, the instructor’s guidance, and the participant’s responses, to immerse listeners in the atmosphere of Pembrey Dry Ski Slope.

After recording, the audio was separated from the video file and exported as a WAV file, chosen for its lossless quality to retain flexibility for any future edits or refinements, as “the WAV file format preserves the highest audio quality, making it ideal for projects requiring flexibility in post-production” (Rose, 2014, p. 92). An MP3 version was also created for compatibility with playback systems during the immersive event. Minimal editing was applied, ensuring the raw and authentic nature of the recordings remained intact, effectively conveying the challenges and triumphs of accessible skiing.

Insta 360 X3 with DJI Mic adaptor, used to capture the audio for the soundscape.

Immersive Event

Beacon’s immersive event title screen.

As attendees enter the immersive room, they are greeted with a title screen welcoming them to Beacon’s immersive event. The side screens display the Beacon logo to maintain brand consistency, along with the QR code, providing a convenient link to all other project platforms and encouraging further audience interaction. A template was used to ensure the positioning of these elements on the title screen was visually balanced and aligned with the overall design of the event.

UWTSD Carmarthen Campus’s immersive room template.

At the beginning of the experience, attendees are presented with a selection of images displayed in a gallery-style format. These images are showcased on-screen, allowing attendees to view them at their own pace while the soundscape plays in the background. This combination of visual and auditory elements is designed to create an immersive atmosphere, setting the tone for the event and drawing attendees into the themes of Beacon.

Version 1 of the images in gallery style for the immersive event.

I expanded the text descriptions to resemble information plaques commonly found alongside images in art galleries.

Version 2 of the images in gallery style for the immersive event.

Following the image gallery, the display transitions to the interview with Ross Head, shown on the back wall of the immersive room.

After the interview with Ross Head concludes, the experience transitions to the 360 immersive video. The Beacon logo has been strategically placed to conceal distracting elements of the 360 video that may appear on the immersive room screens, ensuring a cleaner and more focused viewing experience.

To ensure a seamless experience on the day of the event, we have implemented a series of triggers and actions to automate key aspects of the immersive room presentation. These triggers are programmed to coordinate the progression of media elements, such as transitioning from the image gallery to the interview with Ross Head, and subsequently to the 360 immersive video. By automating these transitions, we minimise the need for manual intervention, reducing the risk of delays or errors during the event.

References:

Ambrose, G. and Harris, P. (2015). Design Thinking: The Act of Thinking Through Design. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Aufderheide, P. (2007). Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beales, F. (2021). The Photography Storytelling Workshop: A Five-Step Guide to Creating Unforgettable Photographs. London: Octopus Publishing Group.

Berger, J. (2018). Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin.

Bordwell, D. and Thompson, K. (2017). Film Art: An Introduction. 11th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Darcy, S. and Dickson, T. (2009). A Whole-of-Life Approach to Tourism: The Case for Accessible Tourism Experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 16(1).

Edwards, E. (2006). The Cultural Significance of Photography. London: Routledge.

Eiseman, L. (2000). Color Messages and Meanings: A PANTONE Color Resource. Gloucester, MA: Rockport Publishers.

Ellcessor, E. (2012). Restricted Access: Media, Disability, and the Politics of Participation. New York: NYU Press.

Evans, E. (2011). Transmedia Television: Audiences, New Media, and Daily Life. London: Routledge.

Everyday Ableism (2024). Everyday Ableism and Its Impact on Inclusion. Available at: https://www.everydayableism.org (Accessed: 8 January 2025).

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman.

Green, M.C. and Brock, T.C. (2000). The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5).

Head, R. (2024). Lecture at UWTSD Carmarthen, 24 October. Personal communication.

Heller, S. (2015). Design Literacy: Understanding Graphic Design. 3rd edn. New York: Allworth Press.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kaplan, A.M. and Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), pp. 59-68.

Kobre, K. (2016). Photojournalism: The Professionals’ Approach. 7th edn. New York: Focal Press.

Landa, R. (2021). Graphic Design Solutions. 6th edn. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Lidwell, W., Holden, K. and Butler, J. (2010). Universal Principles of Design: 125 Ways to Enhance Usability, Influence Perception, Increase Appeal, Make Better Design Decisions, and Teach Through Design. 2nd edn. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers.

Lundberg, N., Taniguchi, S., McCormick, B. and Tibbs, C. (2011). The Benefits of Adaptive Sports and Recreation Participation: A Review of the Literature. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 45(3).

Lupton, E. (2014). Thinking with Type: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, Editors, & Students. 2nd edn. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Mace, R.L. (1998). Universal Design in Housing. Washington, DC: National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research.

Milk, C. (2015). How Virtual Reality Can Create the Ultimate Empathy Machine. Available at: https://www.ted.com (Accessed: 8 January 2025).

Monaco, J. (2009). How to Read a Film: The World of Movies, Media, and Multimedia. New York: Oxford University Press.

Murray, J.H. (2012). Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Murray, J.H. (2016). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Norman, D.A. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things. Revised edn. New York: Basic Books.

QR Code Generator (2024). Dynamic QR Codes: Features and Benefits. Available at: https://www.qr-code-generator.com (Accessed: 8 January 2025).

Rabiger, M. and Hurbis-Cherrier, M. (2020). Directing: Film Techniques and Aesthetics. 6th edn. London: Focal Press.

Ritchin, F. (2013). Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen. New York: Aperture.

Rose, J. (2014). Producing Great Sound for Film and Video. 4th edn. New York: Focal Press.

Sellwood, D. and Coldhouse Collective (2024). Accessibility in Outdoor Media: Best Practices. Available at: https://www.coldhousecollective.org (Accessed: 8 January 2025).

Shah, A. (2021). The Power of Local Media: How Physical and Digital Formats Connect Communities. London: Community Press.

Sobchack, V. (1992). The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Taplink (2024). Create Interactive Landing Pages. Available at: https://www.taplink.at (Accessed: 8 January 2025).

United Nations (2022). Good Practices of Accessible Design in Sports and Recreation. Available at: https://www.un.org/sports-accessibility (Accessed: 8 January 2025).

UWTSD Carmarthen Campus (2024). Immersive Room Template. [Internal resource provided by the University of Wales Trinity Saint David].

Wheeler, A. (2017). Designing Brand Identity: An Essential Guide for the Whole Branding Team. 5th edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.